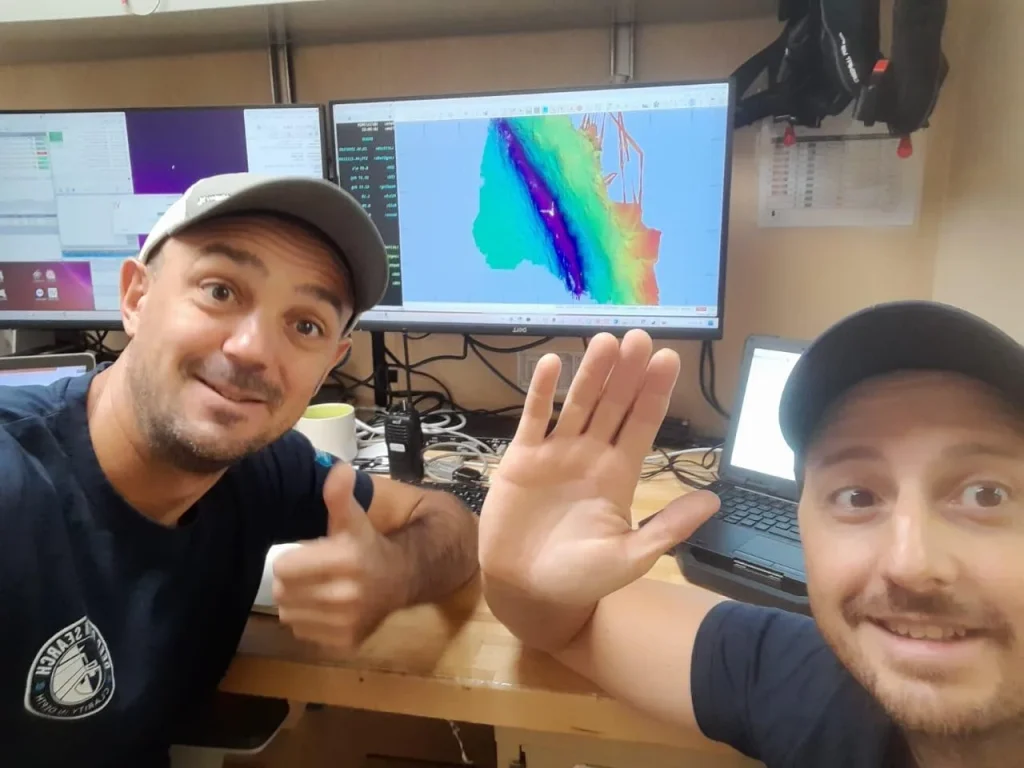

Jérémie Morizet from Manche reached a depth of 10,803m on October 13th 2024, setting a new deep-sea diving record in France. Clément Schapman, a hydrographic surveyor from Rouen, provided support from the surface vessel as part of the project by Deep Ocean Search and InkFish. The pair shared the experience with Normandie Attractivité and discussed their relationship with their homeland, vision of the region and how it supports the maritime industry.

Normandy: a deeper meaning

Jérémie Morizet

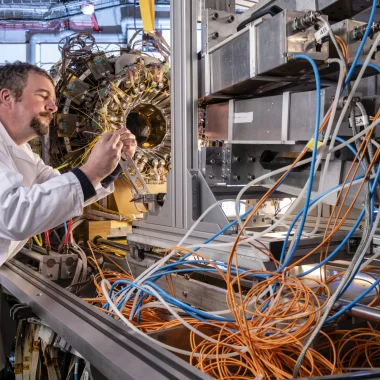

Jérémie Morizet spent his entire childhood in Vernon before going to study at Intechmer in Cherbourg-en-Cotentin. He graduated in ocean exploration and surveying in 2004. His career began at COMEX in Marseille before he joined a new British company that would become Deep Ocean Search, specialising in ultra-deep water activities. Jérémie Morizet still works there as an oceanographer and subsea engineer.

Clément Schapman

Clément Schapman from Saint-Lô, Manche, grew up in the Rouen area before studying at Intechmer, where he met Jérémie Morizet. After graduating, he began his career at a Dutch hydrographic survey company before joining Deep Ocean Search as a hydrographic surveyor and oceanographer. Clément Schapman has been living in Nouméa, in New Caledonia, for a decade.

Does your childhood in Normandy have anything to do with your love for the sea?

Jérémie Morizet : I grew up in Vernon in Eure, but I spent every holiday on the Cotentin Peninsula. I went to the beach, I went sailing. I loved the sea but I didn’t necessarily see myself making a career out of it. My grandfather was an oyster farmer and my uncle was a fisherman in Saint-Vaast, so when I thought of sea-related careers, they were primarily food-related and tough jobs. Intechmer introduced me to the wide array of jobs you could do with the sea…

Clément Schapman : I had the opposite experience to Jérémie. I lived in Manche until I was 6 then I moved to Seine-Maritime. I watched the Armada, I gazed at the yachts and was fascinated by World War II. I’ve now brought my two passions for the sea and history together in my work at Deep Ocean Search.

What do you remember about studying at Intechmer?

JM: There’s no college quite like Intechmer, it’s a bit of a black sheep in the world of vocational courses! The students are in contact with the sea on a daily basis and they just have to cross the road for practical work or a surf on their lunch break! Everyone knows each other at the college, there’s a real community spirit. Intechmer’s courses are world-renowned because the standard of teaching ensures that graduates are ready to work very soon after their studies.

CS: Some of the best years of my life were studying at Cherbourg-en-Cotentin! First of all, the much-respected college is relatively small with a hundred students per year. Secondly, it’s right on the waterfront on Collignon beach. Cherbourg Harbour is an incredible place to learn about maritime jobs! Intechmer has a huge network too: there’s an alumni community and connections all over the globe.

What is your relationship with Normandy nowadays?

JM: I’m often away on expeditions but I still live in Cotentin, near Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, where my family ended up moving to. I’m still very fond of Normandy, I’ve always loved coming home despite the winters being a bit long…

CS: I live in Nouméa but my entire family live in Normandy. I try to come back once a year and this is where I come because it’s where I can truly relax. Living in the tropics means that I sometimes miss the seasons, rain, long summer nights and even Normandy’s winters!

What’s the background to you setting your deep-sea diving record?

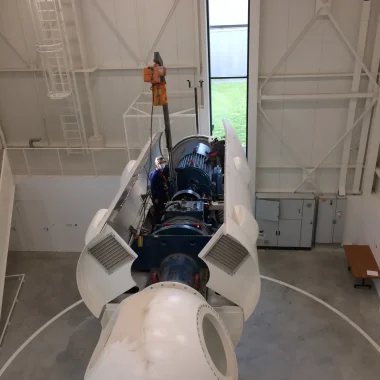

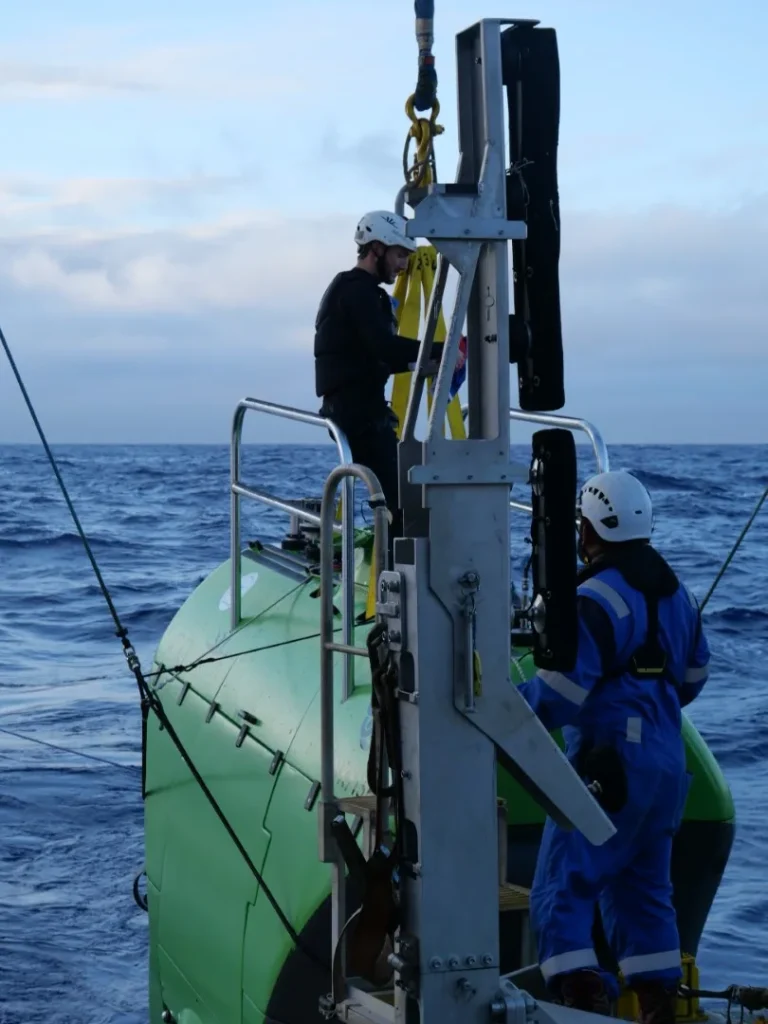

JM: Inkfish, a deep-sea research organisation, contacted Deep Ocean Search a year ago. It wanted to give DOS an underwater acoustic positioning system capable of descending to depths of 11,000m. The original idea was to test out the equipment, not set a record! We had 4 dives scheduled but we only managed one because of the weather. The first and only attempt went swimmingly and we managed to reach a depth of 10,803m. As co-pilot, I also managed to conduct all the tests on the positioning system. There’s always an element of stress because you’re inside a 1.5m diameter titanium pod that will be hit by several tons of pressure per centimetre square of water depth. There’s nothing natural about it. You have to really trust the team in charge of the equipment. But you just focus on the job once you’re in the submarine and in the airlock.

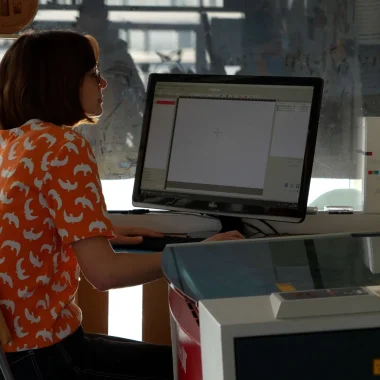

CS: I was on the surface vessel to support Jérémie during the assignment. My role was to coordinate the dive and inspect the standard of the equipment and transmissions. It was a very long dive: it took 4 hours to reach 10,803m, 2 hours to test the equipment and another 4 hours to resurface. So a total of 10 hours of pure concentration.

What can we learn from underwater exploration?

JM: The plan behind this type of diving record is to design new equipment capable of exploring abyssal plains at over 6000m deep. There are only 2 or 3 submarines that can do that at the moment. The deep-sea depths could introduce us to new animal and plant species, new molecules and even new physicochemical procedures (like the recent discovery of dark oxygen), which means it could provide us with treatments for certain diseases, an alternative form of energy and new materials. We have a gigantic field for exploration right under our feet that’s just waiting for us to dive into.

CS: We currently know more about space than we do about the ocean… The ocean still has so much to teach us in terms of science and medicine, as proven by things like algae and its superpowers*. A better understanding of the oceans and particularly the deep sea are essential to better protecting them. There are currently lots of surveying campaigns in international waters to find manganese nodules, a source of great interest among major mining companies. There’s a real risk that the deep sea could be stripped of its resources. Even the slightest change to these marine environments could have an unimaginable impact. Just remember, they’re very slow to regenerate. It would be yet another environmental disaster.

* several Normandy start-ups are currently working with algae i.e. Alga Biologics and MAGMA Seaweed.

You work all over the world. How does the rest of the world see Normandy?

JM: Normandy is best-known for its history and D-Day, but things have been changing recently. The region is increasingly seen as a seafaring land, like Brittany, setting a benchmark in the area for years. Normandy is getting more and more of a name for itself for the region’s maritime industries, shipyards, marine energy projects, sailing events (French Funboard Championship in Urville, Dream’h Cup in Cherbourg etc.), Intechmer… We’re getting the recognition we deserve.

CS: Nobody asks where Normandy is, everyone knows! I regularly sail with Americans, Australians etc. and I’m always surprised at how well they know Normandy and how many of them have already been there to pay tribute to their soldiers. The beautiful coasts, Mont Saint-Michel and Etretat cliffs always dazzle them. Normandy still has a great reputation the world over.

How do you see Normandy’s support to build a better world?

JM: I know there are lots of investment projects in offshore wind power in Normandy and tidal energy is starting to take off. I think this industry in particular could help the region stand out in terms of marine energy, because Raz Blanchard could put us in pole position in the area. That does involve overcoming the technical challenge of how to secure tidal stream generators underwater to withstand the powerful tides…

CS: I had the opportunity to work for the offshore wind farm in Fécamp and saw the investments from Normandy and regional companies in renewable energy and sustainable development for myself. What surprised me were the building sites that have set up in Le Havre and Cherbourg ports for it and how much energy is behind it all. Some people may be concerned about how marine energy could affect the landscape and fishing. But Normandy has the natural resources it needs to do something, we have to move forwards.

Have you seen the direct impact of plastic pollution or climate change on the oceans?

JM: The first time Victor Vescovo, the first owner of the Bakunawa, conducted an underwater exploration mission in the Mariana Trench, the first thing he saw was… a plastic bag. It’s rare in the deep sea but it really hits home. Human pollution is easy to see on the surface. Whole areas in the open sea are covered in macro and microplastics. In terms of the maritime industry and freight, international regulations have seen visible progress for the environment: the MARPOL convention, waste management, eco-friendly oil, a ban on some hydrocarbons, all-electric robots, new wind-powered cargo ships and more. The maritime industry is changing, we’re on the right track.

CS: Unfortunately, you can see plastic pollution in every ocean in the world. Whether you’re in international waters or a remote island in the Pacific, you’re bound to see pollution. There are solutions and they involve prevention, innovation, legislation and community involvement. The only thing that can reduce the impact of plastic on marine ecosystems is us working together. In terms of climate change, the poles are suffering the worst, as we saw on our two exploration missions to find the Endurance. In 2019, we didn’t manage to reach the target area with the ice breaker and had to send a robot under the sea ice. But three years later, in 2022, we managed to reach the same area in the same boat because the ice was far thinner. It’s yet another illustration of the tangible impact of global warming.

Thematics